"VIVALDI AT LA PIETÀ"

In the early 18th century, when Vivaldi’s musical trajectory began, Venice had lost its great economic potential but, regardless, was still a center of attraction for visitors who were taking the “grand tour” of Europe, thanks to its special location, its architecture, and, above all, its culture regarding the art of painting and music.

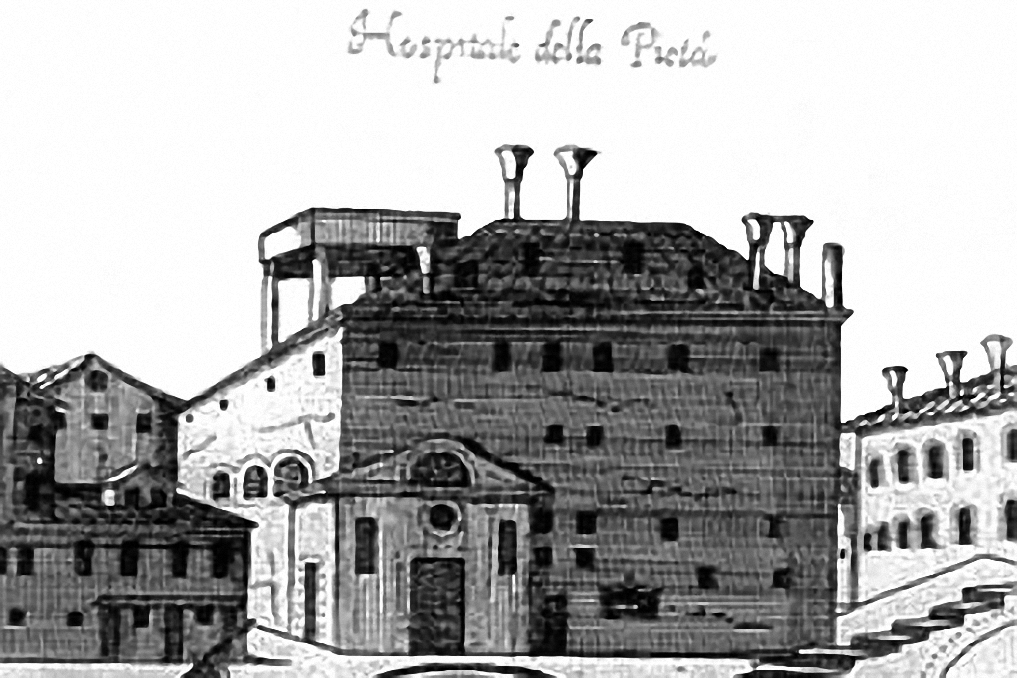

In this musical sphere, the music offered in the “ospedali” was one of the most appealing charms one could find in Venice. The “ospedali” were institutions at the crossroads between orphanages and conservatories, funded by the Republic, and in which the students only were in charge of the performances. Therefore, the ensembles, both regarding vocal and instrumental aspects, were made up of women only (the “figle di choro”). The most well-known of Venetian “ospedali” was one called “della Pietà,” where Antonio Lucio Vivaldi worked as a violin professor and as a “maestro di choro,” between 1703 and 1740.

Strict social regulations prohibited the entrance of male individuals in the “ospedali,” for moral reasons. The only exception was the “maestro di choro.” The word “choro” in that time included the whole ensemble, both the signing voices and the instruments that accompanied them. Petr Andreevich Tolstago, a Russian witness, wrote in 1698 that “one was not able to find such a sweet and harmonious song elsewhere in the world, and for this reason, people from everywhere came to Venice with the desire to be revitalized by these angelical songs…”

Thus, it’s interesting to note that while liturgical music was produced in the Church by male-only ensembles (children, castratos, sopranists, etc.), the music produced in these Venetian locations was solely feminine. The La Pietà’s “choro” arrangement is detailed in a document dated 1707, in which the disposition of the 29 girls that formed the choir is specified: 5 soprani, 4 contralti, 3 tenori, and 1 basso; and the 16 instrumentalists: 5 violini, 4 altos, 2 violette, 1 contrabasso, 1 tiorba, and 3 organists.

The exclusive presence of female voices in the choir probably required that the tenor and bass voices be sung an octave higher than was written, which would have caused slight but odd variations in the pieces’ melodic contour. However, the presence of deep-tuned instruments in the orchestra guaranteed the “harmonic correction” of the ensemble. In this way, the ceremony guests would not have found strange that all chroniclers, many musicians themselves, highlight the extreme beauty of the performance, without noting any type of musical infraction.

It is with these objectives in mind that we present this program with great delight, in order to rediscover the luminous and special sound that feminine polyphony offers. In an attempt to move closer to the original sound, this program is joined by the Scherzo Female Chamber Choir and the Orquestra Barroca Catalana, with historical instruments.

|

1st HALF |

||

|

Antonio Vivaldi |

Tre Salmi |

|

|

|

|

In exitu Israel, RV 604 |

|

|

|

Laudate Dominum, RV 606 |

|

|

|

Laetatus sum, RV 607 |

|

|

Sonata al Santo Sepolcro, RV 130 |

|

|

|

Kyrie en Sol menor, RV 587 |

|

|

|

Credo en Mi menor, RV 591 |

|

|

|

||

|

2nd HALF |

||

|

Antonio Vivaldi |

Gloria en Re major, RV 589 |

|

|

|

|

Gloria in excelsis Deo |

|

|

|

Et in terra pax |

|

|

|

Laudamus te |

|

|

|

Gratias agimus |

|

|

|

Propter magnam gloriam |

|

|

|

Domine Deus |

|

|

|

Domine Fili Unigenite |

|

|

|

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei |

|

|

|

Qui tollis peccata |

|

|

|

Qui sedes ad dexteram |

|

|

|

Quoniam tu solus |

|

|

|

Cum Sancto Spiritu |

Ana Gil-Pérez, soloist

Núria Batet, soloist

Jordi Casas Bayer, conductor